Report title: COVID-19 Lessons Learnt: Recommendations for improving the resilience of New Zealand’s government data system.

COVID-19 lessons learnt - full report [PDF 772 KB]

The research, analysis, and first version of the findings were completed in December 2020.

Stats NZ (2021). COVID-19 lessons learnt: recommendations for improving the resilience of New Zealand’s government data system.

Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa

Wellington, New Zealand

Stats NZ Information Centre: info@stats.govt.nz

Phone toll-free 0508 525 525

Phone international +64 4 931 4600

The COVID-19 pandemic, one of the most significant events to affect New Zealand in recent history, has shone a light on the New Zealand government data system, highlighting existing faults while also providing an impetus for new thinking and offering a pathway to increased resilience.

Taking the opportunity presented by the pandemic, and drawing on a mandate to direct common data capabilities and provide direction to State Sector Public Service Departments and Departmental Agencies (Stats NZ, 2018), the Government Chief Data Steward commissioned Stats NZ to develop a set of recommendations for improving government data system resilience.

In response, Stats NZ captured the experiences of government agencies and international organisations during the pandemic, and documented lessons learnt from those experiences. The synthesis and analysis of the learnings revealed consistent patterns, characterised as four high-level data themes:

The learnings also informed the identification of numerous interventions to increase the resilience of the government data system, and will support a forthcoming proposal for implementing the recommendations.

The government data system represents both the individual government agencies that manage and use data, and the collective of those agencies operating as a single system, with the recommendations designed to apply to both circumstances.

Drawing upon the list of interventions, six recommendations for improving the resilience of New Zealand’s government data system have been proposed:

These recommendations provide a reasonable path forward to start, focussed on a shared outcome (strengthened resilience) benefitting both individual agencies and the collective data system, while creating opportunities for new thinking and innovation. Subsequent actions, drawing from the list of interventions, could further strengthen the level of resilience.

The project referenced six general characteristics of data resilience, garnered from a collection of domestic and international sources, to inform the development of the recommendations:

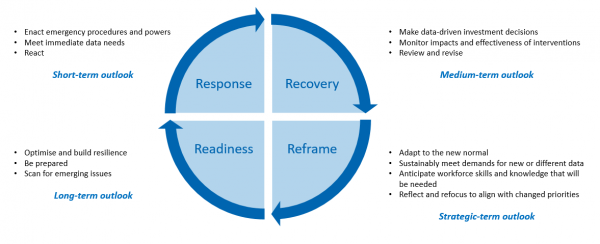

A crisis management resilience model, consisting of four time horizons – Response (short-term), Recovery (medium-term), Reframe (strategic-term), and Readiness (long-term) – was developed in conjunction with the recommendations, to facilitate their optimal implementation.

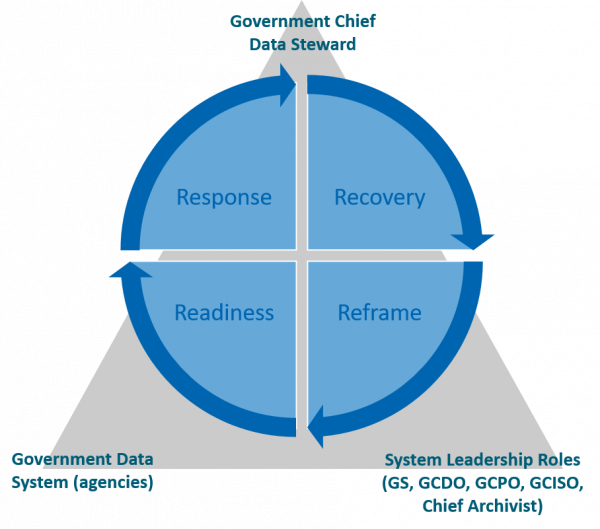

Three classes of government data system roles were designated to provide clarity about responsibilities associated with implementation of the recommendations. These classes consist of the Government Chief Data Steward, the collection of other relevant government system leadership roles (such as the Government Chief Digital Officer, Chief Archivist), and the collection of government agencies.

This paper represents a first step towards improved government data system resilience. Following acceptance of the recommendations, an implementation proposal will provide options for putting those recommendations into practice.

Implementation will involve further user research, close collaboration with Treaty partners and key stakeholders, investments in data and data infrastructure, and the development of a robust and efficient decision-making process with which to guide those investments. The decisions will be challenging, with implications extending into a highly uncertain future, but the analysis of government data system experiences during the pandemic provides valuable insights to inform those decisions.

The COVID-19 pandemic represents one of the most significant events to affect New Zealand in recent history. It has impacted nearly all aspects of life here and abroad, including physical and mental health, economics, travel, trade, housing, communication and politics. It has also revealed the existing disparities experienced by marginalised, at-risk and vulnerable communities. (Kendi, 2020)

New Zealand’s ongoing response to the pandemic has been widely lauded as world-leading. (Koetsier, 2020) This success has been attributed to a number of factors, including our geographic isolation, which afforded us time to assess the pandemic as it unfolded and develop a national strategy in response.

The New Zealand Government also instituted a rapid and decisive move to lockdown, which limited the importation of cases and eliminated community transmission. Since that initial wave of the pandemic, the persistence of international border controls, a stringent approach to quarantining, and contact tracing with genomic sequencing has meant that, as a country, we have been generally successful identifying and isolating new cases and maintaining a level of control over community transmission.

"Starkly and powerfully, the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates how critical data use, with a human face, is to protecting lives and livelihoods. The crisis is a wake-up call."

- António Guterres, UN Secretary-General (2020)

In conjunction with a science-informed approach, data has played a critical role in shaping New Zealand’s COVID-19 pandemic response and recovery efforts.

The wholly new set of conditions thrust upon the country by the pandemic, and the highly dynamic nature of those changes, highlighted the potential of data to an extent not experienced previously. As the pandemic unfolded and demands on them intensified, many government agencies quickly came to appreciate how accurate and trusted data could help them navigate through unfamiliar waters, and manage what was becoming an insatiable appetite for timely information.

In a crisis environment, easily accessible, readily available and trusted data is paramount to formulating a successful response. Decisions and resultant actions, especially during early stages, are often required with atypical urgency, and the availability of data to inform those decisions can either support or significantly impede outcomes, with serious consequences as a result.

The ways in which that data is applied and successfully leveraged during crisis conditions like the pandemic is highly dependent on the level of data maturity of the organisations managing the data.

The overall data maturity of agencies across the New Zealand government data system is currently relatively low and continues to develop. This includes, amongst other things, an increasing recognition that collectively, the data holdings of agencies represent a strategic national asset. It also includes acknowledgement of the accountabilities that come with data and acceptance of the responsibilities associated with those accountabilities.

While not all agencies have contributed to a lifting of data maturity at the data system level, many now do consider their own data as organisational assets with strategic potential. That awareness in itself represents a step towards a more mature view of data, where data system participation is acknowledged and valued.

Under the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the increased demands on their data and the information produced from it, agencies were presented with a convincing case for their role as a participant in the wider government data system. Provided with direct and compelling evidence of the importance of data as a component of a successful response, their awareness of the contribution of data to national resilience (and of data as a national strategic asset) could likewise increase.

System resilience is defined as the ability of a system to anticipate, prepare for, respond, and adapt to incremental changes and sudden disruptions, in order to endure and evolve (Adapted from Denyer, 2017).

It therefore incorporates a range of actions, that are implemented before, during and after an event, with potential to disrupt the functioning of the system.

In the case of a wide-ranging and large-scale disruption, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, there is no single correct path to follow. Events in those circumstances don't typically play out in an orderly or expected way, and there is often little certainty about the appropriate response.

As a result, an effective approach is to increase resilience. If a data system is resilient, it will be well-prepared to react, respond, and iterate, including under conditions associated with a disrupted environment that is ambiguous, dynamic, and unpredictable. While uncertainty may not be eliminated, its negative effects in those conditions can be mitigated.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted several key characteristics of a resilient data system:

Building and maintaining resilience in a data system requires the adoption of different perspectives and corresponding actions at different times, in relation to a disruption event. These can be depicted as four stages of crisis management, each associated with a corresponding outlook time horizon (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Four stages and outlook time horizons of a crisis management resilience model.

This represents the earliest stage immediately following a disruption, characterised by a sense of urgency and the need to act rapidly. In a data system, the focus is on meeting immediate data needs to provide situational awareness, and quickly implementing short-term interventions. If available, emergency powers and procedures are enacted to provide strong leadership, as there is little time for consensus-building. In this stage, agility is key and the associated need for flexibility may mean relaxing consistency, standardisation or other data quality requirements to meet demand.

In this stage the sense of urgency associated with response has started to abate, and the focus shifts to fixing what was affected by the disruption. In a data system, there can be a move towards data-driven investment decisions. Data is used to start monitoring the impacts of the disruption and the effectiveness of interventions. There is room now for investigating changes in data needs, understanding data-related barriers and issues, and identifying medium-term actions to improve resilience.

This stage represents the opportunity to step back and take time for reflection. The disrupted system has started to adapt to a new normal and to changes in priorities. In a data system, demands for new data are being met sustainably, and the knowledge and skills of the workforce are evolving. Strategic planning guides the implementation of necessary long-term changes. With the shift to a focus on stability, the need for consistency and standardisation increases.

In this stage strategic thinking is optimised, with a goal of strengthened resilience. The focus is on preparing for the next disruptive event, in a way that leverages previous learnings. Accordingly, environmental scanning is undertaken to identify emerging issues and opportunities. In a data system, new data and capabilities are developed and instituted where needed, and in response to identified issues and opportunities. Scenario modelling is used to test system responsiveness. Any emergency powers and procedures in place are adapted to reflect identified changes.

In addition to understanding the characteristics of the outlook time horizons and what types of actions are best implemented in association with each, it is also important to designate roles and responsibilities in relation to those four stages.

For the New Zealand government data system, the roles can be organised as follows:

Beyond contributing leadership and accountability in their respective areas, active participation across all of these roles would also foster a more deliberate and consistent system-wide response, reducing uncertainty and ensuring a joined-up approach across key areas like data collection, privacy, human rights and security.

Figure 2 illustrates how these roles and responsibilities are situated across all four stages of the crisis management cycle, ensuring they contribute sustainable leadership and direction as part of an overall resilience approach.

Figure 2. Government data system roles and responsibilities distributed across the four stages of crisis management.

The COVID-19 pandemic was and remains a particularly disruptive event for government data systems, both in New Zealand and globally. The speed with which it became a credible risk, combined with the reach it exerted into so many aspects of daily life, has been unprecedented in scale and impact. The pandemic also arrived at a time of expanded use of and reliance on data within government operations, and increasing acknowledgement of data as a critical asset.

All of this points to the COVID-19 pandemic as a particularly powerful agent of change. And as with any change event, disruptive or otherwise, it also carries with it the potential to deliver positive outcomes.

As the former New Zealand Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor suggested, “Social, environmental, business and geostrategic impacts will echo for a long time and force both global and local change. We must seize this opportunity to have urgent reflection on many issues, not just to recover from the horrific disruption but to find the opportunities for a better future.” (Gluckman & Bardsley, 2020)

Within the New Zealand government data system, the changes that the pandemic necessitated have affected the way agencies engage with data throughout its lifecycle, from planning and collection to analysis and publication, leading to the exposure of new data needs and gaps, a consideration of new approaches, and a reckoning of the ways those agencies engage with and share data.

If considered from the perspective of increasing resilience, the disruptions to the data system can be captured and catalogued to highlight and identify the shortcomings in our current approaches, as well as the innovations that either anticipated and or mitigated negative effects. With improved resilience as a driver, these lessons learnt can be applied across all crisis management time horizons, informing not only the immediate response, but long-term recovery efforts and planning as well.

Recognising this potential, the GCDS commissioned Stats NZ to develop a set of recommendations for a more resilient government data system, drawing on lessons learnt by a range of central government agencies during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

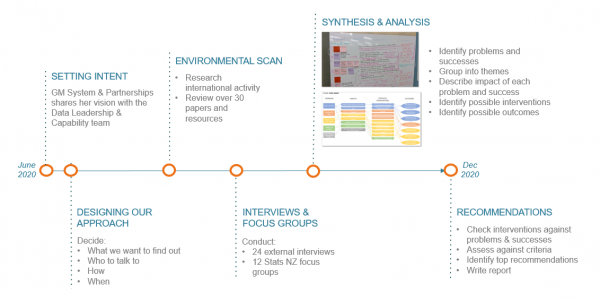

The approach to develop the recommendations (Figure 3) involved four key stages:

Though not in scope for this work, it was anticipated that there would be a follow-up effort, in consultation with government data system agencies, to develop an implementation proposal with details about how the agreed recommendations would be enacted.

It is also worth noting that the recommendations work was carried by Stats NZ as part of its data leadership role, associated with the GCDS, as well as part of its National Statistical Office role, associated with the Government Statistician. This meant maintaining a consistent view of the GCDS as the functional lead role responsible for collaboration and coordination across the government data system.

Figure 3. COVID-19 lessons learnt recommendations project approach.

The initial phase of work comprised a review of available resources that detailed the data-related pandemic experiences and responses of other international and domestic organisations. The key data system characteristics that emerged from this review aligned with those uncovered by the analysis of our interview and focus group results, and are detailed and linked throughout the discussion in section 5.

Interviews were conducted with a range of central government agencies and other organisations that played an important role in the COVID-19 pandemic response and recovery effort, or otherwise had a keen interest in, or pressing need for, data during this time. Perspectives were sought from those working in critical areas of health, education, the economy, and population mobility, as well as those associated with at-risk and vulnerable communities.

The consideration of who to interview also took into account results from the environmental scanning, advice from senior leadership, and the extensive central government agency engagement experience of project team members.

In total, 24 interviews were completed, involving 22 agencies and other groups. (See Appendix 1 for a list of participants.)

In addition to external organisation interviews, the project team also conducted a series of focus groups with 12 different teams within Stats NZ. (See Appendix 1.)

The focus group selection targeted those Stats NZ business units or functional areas with an externally facing role or with a strong customer focus, to capture a view of pandemic experiences from those parts of the data system reliant on central government data and information. It was felt this additional input would add depth to the subsequent results analysis and enhance the relevance of the final recommendations.

Once the interviews and focus groups were completed, the resulting qualitative data was compiled and analysed to identify any consistencies and patterns. Four broad data themes were identified as a result, and a number of actions or interventions were developed within each theme.

The analysis methodology and the interventions were socialised with Stats NZ senior leadership for review and comment, and six final recommendations were identified.

These six recommendations provide benefits for individual agencies and the data system, helping address challenges highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, while serving as an impetus for new thinking and innovation. Enabling the data system to adapt to changing conditions, including disruptive events, will help ensure data can deliver to its potential and play a key role in national response and recovery efforts.

Once the recommendations have been socialised and published, Stats NZ will work with agencies to develop an implementation approach and action plan. As part of that work, we anticipate situating the recommendations in terms of:

Implementation of the recommendations will involve investments in data and data infrastructure by agencies across the government data system, so will therefore need to be realised in a coordinated manner. One means of facilitating that will be to ensure that implementation efforts reflect and draw from data system work currently under way at Stats NZ, including:

It is anticipated that the GCDS will oversee agency actions associated with implementing the proposed recommendations, as part of its data system leadership role to foster collaboration and coordination between agencies, and promote data best practice. The GCDS will also consider options for monitoring agency implementation efforts, with a goal of demonstrating and tracking real progress towards a more resilient government data system.

This section provides the final set of recommendations, organised under four high-level data themes. Each data theme also includes additional information gleaned from the environmental scan and the collection of agency lessons learnt experience, to enable a more detailed understanding. This includes:

To support a rapid and effective response to a crisis, government data must be readily available, easy to use, and able to be shared between agencies and with the public as appropriate.

A robust and well embedded data infrastructure is paramount for facilitating this ‘frictionless’ flow of data. If adequate exchange mechanisms are not in place, there is a risk that sensitive data will not be managed securely. Without sufficient infrastructure, there is the added risk that the most relevant data will be missed, potentially impacting the quality of subsequent decision-making.

During the pandemic and under unprecedented demand, there were many examples of successful data exchanges between government agencies and the development of innovative approaches to facilitate sharing.

Agencies with existing data sharing agreements and processes were able to employ those to source new data or establish a timelier data supply. Those with ties that extended outside of government found those relationships particularly valuable for accessing the full range of data needed to properly respond to demand.

Agencies in the transport sector, for instance, were able to efficiently access data from a range of sources, and use that data to provide timely advice to their Minister. This was only possible because they were able to leverage previous investments in agreed standards and other data infrastructure.

Some agencies also accessed data via analytics services such as Stats NZ Data Ventures, which brokers relationships between government and the private sector. The access to insights derived from private sector data increased the level and quality of information available to support subsequent decision-making.

In some cases, data fees were waived for the duration of lockdown, to support easier and more rapid access. Microdata access was provided remotely for approved researchers working at home, and some agencies were able to share their data lab space.

Several agencies quickly developed new data products and visualisations, using their existing toolsets, to provide insights on a range of topics.

When exploring the economic and social impacts of the pandemic, some agencies published additional commentary to describe new data sources or changes made to existing data. This was important to avoid misinterpretation of the results and provide trust and confidence in the data and processes used.

The Stats NZ COVID-19 data portal, quickly stood up to provide easy access to pandemic-related data and information, was well received and provided a useful one-stop shop and source of frequently updated private sector data.

Agencies that had already invested in data warehouses and analytics were able to quickly adapt their systems to create new reports, while agencies relying on legacy systems or with gaps in infrastructure were hindered in their response.

Inland Revenue, for instance, had started to invest in business intelligence capability as part of a business transformation initiative prior to the pandemic, which enabled them to quickly stand-up internal reporting tools to track impacts within their organisation and for the services they provide. (See Establishing a self-service data portal case study below.)

The National Crisis Management Centre (NCMC) utilised existing geospatial infrastructure and data, which allowed them to perform analysis using different geographic boundaries. The subsequent increase in the use of data helped highlight its importance and mark it as a focus for investment.

Case study: Establishing a self-service data and information portal.

A few agencies were unable to share data because they lacked a safe mechanism to do so. In other cases, data was shared despite these shortcomings, due to urgent need. Some agencies expressed confusion at the variety of exchange methods available and indicated they would welcome clearer guidance on which methods are considered secure or are preferred.

Agencies employed different risk profiles to establish new data sharing agreements during the pandemic, with some choosing to involve their legal teams. In some of those instances, the addition of a legal perspective shifted the agency to a highly risk-averse stance, which slowed or halted sharing efforts, impairing its ability to meet demand for timely and easily accessed data.

Several agencies noted that they were unsure what data could be shared under the Privacy Act, and the Government Chief Privacy Officer received numerous requests to help agencies navigate this issue. Despite the Privacy Commissioner publishing advice on the use of privacy codes to support data sharing during a state of emergency, many agencies remained unaware of these provisions. (Edwards, 2020)

In an environment of uncertainty, perceived and technical barriers associated with sharing sensitive data took on added significance, and in some cases resulted in an agency only sharing aggregated data. Because the mitigations needed to address crisis challenges are often most effectively applied at the local level and to specific challenges, they require granular data at a similar scale. Aggregated data proved to be of limited usefulness in those cases.

To address these challenges and facilitate effective data sharing during a crisis, one agency suggested that a consistent sharing framework be developed and implemented across government.

There was increased demand for access to microdata during the crisis which, despite prioritisation efforts, created a bottleneck in some parts of the system. Where microdata was shared, the lack of standards adoption (both across the system and within sectors) led to more work in wrangling the data.

In some cases, data could not be integrated. The lack of consistent collection of key attributes, like ethnicity for instance, made it difficult to integrate datasets for a pandemic view of at-risk communities. While new data related to the pandemic and in service of the government response was proactively released, it was not always made available in the most readily usable format.

During the pandemic, smaller agencies suffered from their lack of infrastructure for collecting, sharing and analysing data. Some agencies managed to adapt existing operational systems to collect data, whereas others had to use publicly available cloud services to meet data needs.

Agencies that worked with community organisations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) also reported ongoing gaps in the infrastructure required to collect data about the people for whom they provide services.

Some of the tools and processes developed by agencies in the urgency of the response are not sustainable, and would require either manual intervention or additional investment to be maintained in the medium term. What’s more, existing system infrastructure like data.govt.nz was not used to its full potential during the crisis, potentially due to a lack of awareness.

Internationally, governments are increasingly realising the value of integrated data in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic and are investing in infrastructure projects in response, to build up their capability. (Berkowitz & Katz, 2020) The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) in the United States recently announced investment in a platform to bring together and integrate health data from across the country, using a standard format. (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, 2020)

Providing access to data and transparency of impacts and responses has been a key focus of the open data community (OECD, 2020) as well as international cooperation organisations such as the OECD, IMF, WHO and UN. (United Nations, 2020) During the pandemic, the approach to open data has varied among countries, states and cities. Most governments provided public dashboards with daily updates to monitor the spread of the disease. Some governments also provided greater access to utility data, such as the location of essential services like supermarkets, pharmacies and petrol stations. (National Institute of Statistics and Geography, Mexico, 2020) In New Zealand, a few regional councils provided this type of data, but they were the exception rather than the norm.

New Zealand proactively released epidemiological modelling reports (Ministry of Health, 2020), as did other countries including Scotland, Ireland, Canada and some states in Australia. In Melbourne, which experienced a lengthy second wave of the COVID-19 coronavirus, the model used to inform city-wide lockdown decisions was published in a peer review journal and was the subject of much commentary and analysis. (Gans, 2020)

Some of the perceived data gaps uncovered during the pandemic were due to users not being able to find or access existing relevant data. Information about data is currently held in several repositories located around the government data system. Efforts to make these repository resources more broadly visible and readily accessible would help address this gap. This would require a multi-dimensional approach, including improving findability, building data skills, enabling access, raising awareness, and developing a support network of key contacts and data experts.

Some of the perceived data gaps uncovered during the pandemic were due to users not being able to find or access existing relevant data. Information about data is currently held in a number of repositories, located around the government data system. Efforts to make these repository resources more broadly visible and readily accessible would help address this gap. This would require a multi-dimensional approach, including improving findability, building data skills, enabling access, raising awareness, and developing a support network of key contacts and data experts.

The Stats NZ Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) enjoys a high profile amongst the user community, illustrated by the increased demand for IDI data during the response. However, many of the requests for data directed to the IDI could also be met through other tools and services, perhaps more efficiently, acknowledging that source agencies have different protocols and processes for providing access to their data.

There are multiple, and sometimes ad hoc, ways that data is currently shared between agencies, and it isn’t always evident how these methods protect privacy, confidentiality and security of the data.

This theme describes the successes and problems government agencies experienced when using data to meet information needs arising from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data is needed in any crisis to help understand the impacts of the crisis and the proposed interventions. Timely, local data on specific communities, especially those most at risk of adverse impacts, needs to be readily available, exhibit the appropriate coverage and level of quality, and be well-described.

Data can be more efficiently and effectively leveraged if users can easily locate the data they need, are aware of available data collection mechanisms, and can readily assess data quality.

Agency pandemic responses included examples of innovations, where new data was used or existing data was used in new ways, and data gaps, where data was either missing, not timely enough, or not of adequate or fit for purpose quality.

Data adequacy gaps included:

Having the right data at the right time helps decision-makers to make more informed decisions more quickly. If the data is late, missing altogether, or of inadequate quality, this can reduce the confidence in the decisions made based on that data, and potentially cause adverse or unintended impacts for communities associated with the data.

While these data adequacy issues were not new, the nature of the pandemic crisis and the associated need to respond quickly at a local or community level tended to give added prominence to the issues and exacerbate their effects.

"Without good data, planners can't plan, epidemiologists can't model, policy makers can't make policy, and citizens don't trust what we're told."

Davenport, Godfrey, & Redman, 2020

The identification of those considered at risk will vary, depending on the nature of a crisis or disruption. For example, those adversely impacted by widespread drought may be different from those impacted by a pandemic. The definition of vulnerability can also change as more is learned during the transition from response to recovery. For example, those aged over 70 years were considered most at risk in the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic; this has now changed to those aged over 80 years.

During the pandemic, agencies used numerous data sources, from different domains and often in innovative ways, to understand health and economic impacts, and wider social and cultural implications. (Davenport, Godfrey, & Redman, 2020)

Some data needs were met in an efficient and collaborative manner, by adding new questions to existing collection surveys. In other cases, new data sources and methods were used to supplement data that couldn’t be collected using traditional means, due to social distancing restrictions or the desire to avoid burdening people and businesses already under stress. For example, traffic volume data was used in a new way to create an economic indicator.

New data was sourced from both the public and private sectors to provide hourly and daily updates, and this data proved highly valuable for measuring behaviours during the different alert levels. Updates to existing data were also supplied at greater frequency, although often with additional quality caveats.

Pre-pandemic investment in data infrastructure and capability enabled more mature government agencies to leverage data to quickly create new views, publish dashboards, and create data products used to inform reporting and decision-making.

In addition to the coverage issues noted above, there were other data gaps identified, including but not limited to, data on international students, foreign nationals, the digitally excluded, and data related to services provided by NGOs.

When data did exist about at-risk communities, the disaggregation required to make it useful was often not possible. This made it difficult to understand and measure impacts on local communities. In the case of New Zealand’s disabled population, data gaps were increased by the collection methods used or digital services implemented, as these were not designed to be accessible to many members of that community.

Gaps in wellbeing data, especially data reflecting mental health, were difficult to fill from administrative data sources.

Geographic breakdowns tended to be based on available administrative boundaries, which did not necessarily reflect or effectively capture the mobility patterns associated with people’s everyday lives. The private sector in some instances was willing to provide data to address these gaps and support the ‘public good,’ but the sustainability of these arrangements beyond the context of the pandemic response remains unclear.

For government agencies that operate with a decentralised model, data collection can be inconsistent across offices, resulting in patchy coverage and unreliable levels of quality. During the pandemic, this made it difficult to collate data into a national view.

Real-time and near real-time data was of particular value to agencies during the initial response of the pandemic, as it was required to capture the highly dynamic changes that characterised early stages of the crisis. While some data of this frequency was available, many agencies expressed a desire for more, particularly in the economic domain.

During the initial stages of the pandemic, many agencies independently developed surveys to collect data that would help them understand impacts on their constituents and customers. While this approach enabled rapid gathering of useful data, the lack of coordination between agencies resulted in some duplicated efforts and at times, increased respondent burden. It also meant that content standards which support the collection of interoperable and properly disaggregated data were not implemented consistently, or in some cases, at all.

Since then, the GCDS has provided collection guidance to increase coordination and interoperability across the government data system. (Stats NZ, 2020)

Agencies with a good knowledge of what data exists in the system, and options to leverage networks and relationships with other agencies, were able to source data relatively easily. However, some agencies struggled to know who held what data or what data they needed. Some of the new data sources used in the pandemic were untested and not well documented, so analysts had to spend additional time cleaning the data and assessing its quality.

Case sudy: Reflecting communities of iwi and Māori, Pasifika, and people with disabilities.

The adequacy of data to reflect at-risk communities is highlighted in the international literature on the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, it has been noted that access to information about at-risk communities was needed to both inform the government response and to help those communities look after their own people. The city of Chicago, for instance, used data broken down by ethnicity and geography to help understand disparities in case rates and address misinformation about who was vulnerable to the virus. (Lucius, 2020)

The mis-categorisation of indigenous and minority populations was also cited as a factor in exacerbating existing inequalities in services. (Russo Carroll, Rodriguez-Lonebear, Akee, Lucchesi, & Richards, 2020) Many countries used experimental data sources (such as mobility data), and provided additional commentary to help customers understand the changes in official statistics (including excess mortality) or the quality of new data sources. (Statistics Netherlands, 2020) Some countries also created bespoke data products to understand the pandemic’s impact on at-risk communities. (Office for National Statistics, 2020)

The pandemic has demonstrated that work is needed to improve the coverage and quality of data within the government data system so that it is genuinely inclusive, and that this is best done in collaboration with stakeholders and communities.

This collaboration will inform decisions about what data is needed and collected and for what purpose, and will lead to increased understanding about data needs in the response stage versus the recovery stage. For example, while initial response data needs might focus on quantifying impacts (often in real-time), the recovery stage’s needs might focus instead on measuring progress.

Increasing data coverage in this way requires lead-in time before collection improvements are realised, to establish relationships, and collaboratively plan and design. That lead-in time needs to be factored into investment decisions.

Work on a Data Investment Plan is currently underway at Stats NZ, with the aim of ensuring government has the data it needs to assess the wellbeing of New Zealanders and the state of our economy and environment. The data needs that surfaced during the pandemic response and those that result from implementation of the recommendation listed above will need to be reflected in this data plan.

Data needs to be described adequately and in a standardised way, to help users to understand and interpret it, and more easily make informed decisions when using it. Key to this understanding is knowing when data is fit for purpose.

Coordination and robust governance are essential for enabling government to respond effectively and decisively to a crisis, while maintaining public trust.

The limited resources of government, combined with the additional pressures that the COVID-19 pandemic placed on the country, means increased coordination between government agencies is required to minimise burden for constituents and customers, and maximise effort and impacts.

The processes for decision-making also need to be efficient and consistent to support a quick response and ensure risks are considered appropriately. The increased use of new and existing data sources for new purposes requires good governance at both the strategic and operational level.

"Conditions of high uncertainty require effective interorganisational communication and collaboration to help provide a more holistic sense of poorly understood and evolving new circumstances."

Lips & Eppel, 2020

Many agencies formed new relationships or strengthened existing ones with their data suppliers, stakeholders and customers, in response to the pandemic. This resulted in more timely data supply and a better understanding of data needs, both immediate and ongoing. (Lips & Eppel, 2020)

Some of these emergent needs were met through collaborations implemented across government, such as the New Zealand Activity Index (a joint effort between The Treasury, the Reserve Bank, and Stats NZ) which provided more timely economic data. (The Treasury, 2020) In some agencies, the pandemic has created a new focus on continuing relationship-building, or expanding existing operational relationships to foster strategic cooperation.

Case study: Pooling agency capabilities and data to meet demand

Existing data governance and advisory groups were used to share information about agency activity during the crisis, and helped to prioritise microdata access requests and the sourcing of new datasets for the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI). New data sources were provided to agencies through a service provided by Stats NZ Data Ventures, which also helped broker new private data sources on behalf of the public sector. This avoided the use of multiple, redundant approaches.

Within some agencies, decision-making and processes to approve new uses of data were streamlined.

Across government, many data-related groups continued to meet online during lockdown and share information about their activities and the challenges they faced. The GCDS provided a collaboration site to improve visibility of agency data activities and encourage cooperation across the data system, which was well-received during the response stage of the pandemic.

Especially at the very onset of the pandemic, many agencies lacked visibility of data-related activities happening across the government data system. In the initial rush for data, duplicate data requests were not uncommon. All requests were considered urgent, so it was difficult to prioritise.

While some agencies cooperated with one another to facilitate joined-up data collection, there were also numerous surveys employed by individual agencies to meet their own specific data needs, particularly in the wellbeing space.

The resultant siloed, and in some cases redundant, approach to data collection increased the burden on respondents in some instances and negatively impacted their trust and confidence in the government. In one case, a hasty approach to collection was linked to poor quality results.

One agency suggested that having ready access to clear guidelines or standards for survey collection would have allowed them to quickly apply that advice during the pandemic.

Agencies were also conscious of issues of data governance and social licence during the pandemic, but were uncertain about when and how to address them. Some agencies commented that it was difficult to know who had authority to make decisions in the data governance space. The NCMC approached existing data governance groups to see if they could provide authority for data-related decisions, but found they were not set up to do so.

There was some confusion about who to go to for advice on data issues, with agencies approaching the Privacy Commissioner, Government Chief Privacy Officer (GCPO), Government Chief Digital Officer (GCDO) and Government Chief Data Steward (GCDS). This meant in some cases that requests had to be redirected to the appropriate agency, slowing their resolution.

Despite the call for help across government, some agencies felt their expertise was not well understood or was underutilised. Advice services such as the Data Ethics Advisory Group were also undersubscribed during the crisis.

Unable to access clear advice or an authoritative body, agencies defaulted out of caution to a highly risk-adverse position, fearful of losing social licence. This in turn may have restricted or limited the application of innovative solutions that could have better met needs during the pandemic.

Work is required to understand the social licence implications of data sharing during a crisis, particularly when short-term arrangements enacted in a response stage are extended into the recovery period. This will lead to increased understanding of the ongoing impacts of the crisis.

Transparency in providing open access to data about the government’s response to a crisis is essential for maintaining trust and holding the government to account. This is particularly important during a crisis like the pandemic, since the government’s decisions in those circumstances can have significant and long-term impacts on the lives and livelihoods of a large portion of the population.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced several countries to rethink how they collect data. The Canadian National Statistics Office has been exploring a range of new data sourcing models such as crowdsourcing, and working with other agencies to develop new approaches. (Hunt, 2020)

The NYC Recovery Data Partnership was established in New York City to coordinate and facilitate data sharing between community, non-profit, and private organisations, resulting in valuable data for use by the municipal government. (Mayor's Office of Data Analytics)

Numerous commentators in the data and technology space have highlighted the importance of data governance, and the role of Chief Data Officers in helping their organisations navigate and respond to the opportunities and risks presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. (Vincent, 2020)

In the UK and Europe, agencies have published privacy statements about how they are managing contact tracing data in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). (NHS Digital) Legal consulting firms have also published guidance on how to meet privacy obligations during the pandemic. (PwC Legal, 2020)

In the academic community, the ethical implications of new data sources such as contact tracing are under review, with emerging awareness that, in addition to privacy, issues of autonomy and inequality also need to be considered. (Gasser, Ienca, Scheibner, Sleigh, & Vayena, 2020) Others have argued that the pandemic crisis is compelling us to move beyond individual-based consent approaches to data governance. (Renieris, 2020)

Reacting quickly and decisively to a disruptive event like the pandemic requires working together, and pooling resources and expertise. Knowing who makes decisions, who to approach for advice, or where to inquire about data availability, and getting a timely response, is critical. Without this awareness there is a risk that subsequent actions are taken with incomplete information, have a narrow focus of only resolving the problem at hand without considering the wider context, or duplicate the actions of others.

During the pandemic, there was an appetite for unequivocal leadership and improved guidance on data governance arrangements designed to empower agencies to act quickly while meeting legal and ethical obligations. More clarity is needed on the responsibilities and authority of the different data governance roles and groups, particularly during the initial stage of a crisis event.

Map and rationalise the key data governance arrangements within the government data system, and develop a means of maintaining and sharing this information.

This work would include defining responsibilities and powers during the response stage, and providing advice on whether or how these roles might change in the transition to subsequent crisis management stages.

A catalogue resource like this could be used to answer questions like: Who should someone talk to when trying to source new data? Who should coordinate engagement when trying to source data from the private sector? How might government ensure a broader perspective so that the needs of the wider data system are considered?

This theme captures the problems and successes associated with what can be broadly characterised as people skills.

To empower people to use data, they need to have the capability to understand, assess, analyse and communicate the data. Without these skills, data may be misinterpreted, or an inherent bias may be undetected - what’s wrong in the data may be obvious, but what’s missing may not be.

The COVID-19 pandemic has reaffirmed the increasing understanding that it is not just data analysts that need to be data literate, but also policy analysts and decision-makers using the data.

Government agencies exhibit varying levels of capability and capacity for data analytics and other data-related skills. Consequently, the government needs to carefully manage its resources to ensure it can meet data needs when required.

Data expertise was shared across government, as a result of the wider call for assistance that went out to agencies, and through informal sharing of staff between those agencies already working closely together.

While a relatively minor factor, the beneficial results of the sharing of expertise between agencies were diminished somewhat due to the challenges of shared staff working in unfamiliar environments and their associated lack of domain knowledge.

Within agencies, prioritisation models were developed to help manage staff workloads, particularly for those providing skills in high demand.

The need for more timely data led to innovation in how agencies shared, processed, used and published data, which in turn resulted in new resourcing approaches. As a smaller agency with limited capacity, and in response to a high level of demand, the Ministry for Women for instance outsourced their policy research to help provide context and commentary on the impacts of the pandemic on women.

Overall, the pandemic crisis provided a strong impetus for the rapid upskilling of staff and helped to lift capability in less data mature agencies.

There were some examples where existing system guidance and expertise were leveraged to support data literacy during the pandemic response. The Ministry of Education incorporated the Data Protection and Use Policy (DPUP), developed by the Social Wellbeing Agency, as part of their data management framework. (Social Wellbeing Agency, n.d.)

The GCDO and GCDS functional leads were approached for their advice on data sharing, although in general these services were undersubscribed, possibly due to a lack of awareness.

While agencies recognised the need to prioritise timeliness over quality, some agencies were not sure whether the quality of data they did use was adequate, and didn’t have time to sufficiently consider the data from a quality perspective. There was concern that this could erode confidence in the data over time.

As a solution, one agency suggested the use of a quality matrix to convey the level of risk associated with different data sources, and the appropriate uses of that data.

In the early stages of the pandemic crisis, some agencies struggled with having to ‘make do’ with the data that they had to collect under high demands for decision-making, which was of lesser quality due to inadequacies in the data itself or their difficulty accessing the data.

Agencies with higher levels of analytical capability tended to be more confident with the quality versus timeliness trade-offs they had to make, whereas agencies who were still developing their analytical skills experienced persistent uncertainty.

A few agencies were not sure of what data skills they needed, and some agencies were unsure about what data could be collected or shared while still meeting privacy obligations. Limited capabilities in data analytics, data visualisation and data storytelling were the most often cited skills gaps, particularly to support communications from decision-makers.

The additional effort required to understand new data and new analytics on top of regular work contributed in some instances to increased pressures and workload for staff. Some agencies struggled to optimise their processes, due to legacy systems or lack of capability in automation, which meant more manual work was required, especially for frequently updated datasets.

The redeployment of staff also contributed to greater work pressures in their usual teams by increasing workloads and creating skill gaps, especially when those teams had to continue with their business-as-usual work.

Community organisations, especially those delivering services on behalf of government, need to be better resourced to build their own data capability and make effective use of data.

There are a number of frameworks, legislation and policies of relevance across the government data system (for example, PHRaE[4], DPUP, Ngā Tikanga Paihere[5], Privacy Act), and navigation of them can be difficult and time-consuming for data users trying to understand what should and shouldn't or can and can’t be done with data. Proper awareness of these frameworks and policies and their appropriate use currently varies across government agencies.

Internationally, demand for data analysis and modelling skills has increased during the pandemic. In response, several governments have collaborated with the academic and private sectors to boost their capabilities in these areas.

The UK government partnered with the Royal Society, which put out a general call for data modellers. (Royal Society, 2020)

The Canadian government worked with a firm specialising in artificial intelligence (AI), which was one of the first to identify the threat of the virus. (Vendeville, 2020)

Some countries also held data hackathons to harness the talent of the wider data community and get citizen input to help address community issues. In the United States, several state governments have been actively recruiting to increase their data capability in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. (Lally, Valenta, & Jogesh, 2020)

The pandemic highlighted the need to build data skills and knowledge across government, in areas such as analytics, data ethics, privacy, security, and storytelling. Leadership and training are needed to help develop a culture where data safety and ethics is embedded in data use and governance. This is a requirement for agencies also supporting agile ways of working, including the ability to switch between operating contexts that require different quality standards.

Possible options for addressing these needs include developing guidelines and resources, providing access to experts and training, and facilitating the sharing of knowledge.

The Government Economic Network (GEN) and Government Analytics Network (GAN) represent two examples of existing expertise-based government networks, though the GAN is currently inactive.

Additional networks or communities of practice may also be beneficial. For example, data visualisation and storytelling, data quality, data wrangling, and data collection are all areas of need that could benefit from a practitioner community. Any networks that are established need to be adequately resourced to maintain them and keep them viable.

Having the appropriate knowledge plus supporting guidelines and checklists is essential to ensure the correct security, privacy, and ethics checks and balances are maintained, while agencies work at pace in the response stage.

In implementing this recommendation it’s necessary to identify what’s needed to ensure that, across the government data system, at least a minimum level of data ethics, privacy, security, and safety checks and balances are in use.

Initially this work could involve the development of a set of guidelines and checklists, which could then be expanded based on feedback. Also needed are resources that provide a compelling case for why these data considerations are important. Knowing that this documentation exists, is readily accessible, and promoted within agencies, will contribute to increased public trust.

Because these considerations shouldn’t be set aside in a crisis, also explore how best to refer to them during the response stage of a crisis. For example, consider and agree what items like this might be included in a relevant data checklist for use in these situations.

To make the best use of talent, a more coordinated approach to capability management could help with sharing expertise and domain knowledge across agencies.

Possible options for answering this need include developing guidelines and resources, providing access to experts and training, and facilitating the sharing of knowledge.

The recommendations and additional interventions proposed in this paper are meant to guide those agencies participating in the New Zealand government data system towards increased resilience. A genuinely resilient data system will be well placed to adapt to changing conditions, including new disruptive events that might affect New Zealand in the future, ensuring data can deliver to its potential and play a key role in our national response and recovery.

The efforts that will be required to implement these recommendations, and the changes within agencies and the broader data system that could result from those efforts, need to be considered within each of the crisis management resilience model time horizons (section 3.1). This promotes a holistic view of the way data can contribute to the national agenda, and it is through that approach that a persistent and sustainable resilience will be achieved.

The recommendations and interventions proposed in this paper reflect a mix of those linked directly to the results of interviews and focus group sessions, and those the project team contributed based on their extensive experience in the government data system and their roles as data thought leaders.

Recommendations that most significantly draw from specific experiences of agencies operating during the early lockdown stages of the pandemic are likely to be more amenable to response and recovery time horizons. Other recommendations, incorporating less of a situational and a more of an inherently sustainability-based perspective, are likely to map naturally to the reframe and readiness time horizons. Therefore, when considered in full, the list of recommendations and additional interventions should provide a means of delivering value across all of the resilience model time horizons.

As the implementation of these recommendations is considered, it is important to keep in mind the key characteristics of a resilient data system noted in Section 3. These characteristics reflect the experience and lessons learnt from organisations in different contexts around the world, also struggling with the new post-pandemic reality.

These characteristics can serve as a reference, helping to confirm the viability of the recommendations that are adopted, and characterising the progress of implementation plans that result. More strategically, they offer direction for developing a consistent and targeted set of goals to apply across the government data system. If leveraged in this way, they could potentially save time and effort on the journey towards resilience.

If the recommendations are to be successful as drivers of change for increased resilience, they need to be implemented in an environment where data is considered a national asset. This requires proper socialisation of that view across the New Zealand context, including at the highest levels of government, so that messaging about the inherent importance of government data emanates from the top.

This is especially important in a crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic as an example has already demonstrated the immeasurable contribution of data to a successful crisis response, even before the understanding of data as a national asset has been widely adopted in New Zealand.

As it happens, government has an established mechanism – a national emergency management system – at our disposal to more deliberately promote the role of data as a strategic asset in a crisis, and as a key to strengthening resilience. During the COVID-19 pandemic, and with little advanced planning, that emergency management system was leveraged to implement useful innovations, including the development of a 4-level Alert System, and daily leadership communication briefings.

Likewise, the administration and promotion of government data could readily become part of that emergency management system, bolting onto existing infrastructure. Constituent elements like a centralised data authority could be activated, potentially under emergency powers, to help manage the collection and use of government data as part of a national crisis response.

In this scenario the GCDS, as the government’s functional lead for data, would have an authoritative role to direct and coordinate data-related activities across the government data system. Alongside that leadership role across government agencies, there is also the potential for a public-facing component, similar to that of the Director-General of Health during a health pandemic.

Public briefings by the GCDS could be used to promote data as a national asset, as critical as other, more familiar national infrastructure, and especially important in managing our response to a crisis. These briefings could also provide the public with a level of government transparency, offering assurance about how data is being used responsibly, with protections in place.

This is an especially important message during a crisis response, helping to maintain social licence when there is higher demand for data. This sort of public communication could help the GCDS proactively address trust issues, like those that have affected uptake of the NZ COVID Tracer app.

Ultimately, the outcomes resulting from the adoption of the recommendations proposed in this paper will manifest as investments in data and data infrastructure, and in the development of a decision-making process for those investments. It is with that lens that the recommendations should be considered.

The challenge facing government agencies in this regard will be associated with developing sufficient confidence in their investment decisions, and supporting resultant investments in a manner that clearly contributes to strengthened resilience. It is no easy task to move ahead with investment decisions based on future scenarios that, as the COVID-19 pandemic has driven home, are highly uncertain.

More specifically, it is difficult to know how to distribute investments between those that can be used to generate sustainable change, applicable and effective during both crisis and peacetime, and those that need only deliver to demands unique and limited to the immediate response stage. Too much emphasis on long-term change can result in wasted spending, while too much emphasis on short-term needs risks spending on the same issue multiple times and with each crisis event.

Faced with the need to make investment decisions that extend into an unpredictable future, one reasonable option for agencies is to investigate and learn from what has happened in the past. It is from that position that the work to develop these lessons learnt recommendations was initiated and is offered for consideration.

It is the hope that the proposed recommendations can provide a level of direction and guidance to agencies in the government data system in support of successful investments, and in a broader sense demonstrate the inherent value of data to New Zealand’s national resilience.

Berkowitz, E., & Katz, M. (2020, September 1). How Integrated Data Can Support COVID-19 Crisis Response and Recovery. Retrieved from Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy: https://aisp.medium.com/how-integrated-data-can-support-covid-19-crisis-and-recover-35d981d3a708

Davenport, T. H., Godfrey, A. B., & Redman, T. C. (2020, August 25). To Fight Pandemics, We Need Better Data. Retrieved from MITSloan Management Review: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/to-fight-pandemics-we-need-better-data/

Denyer, D. (2017). Organizational Resilience: A summary of academic evidence, business insights and new thinking. BSI and Cranfield School of Management. Retrieved from https://www.cranfield.ac.uk/~/media/images-for-new-website/som-media-room/images/organisational-report-david-denyer.ashx

Edwards, J. (2020, October). Civil Defence National Emergencies (Information Sharing) Code 2020. Retrieved from Office of the Privacy Commissioner: https://www.privacy.org.nz/privacy-act-2020/codes-of-practice/cdneisc2020/

Gans, J. (2020, September 8). The modelling behind Melbourne's extended city-wide lockdown is problematic. Retrieved from The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/the-modelling-behind-melbournes-extended-city-wide-lockdown-is-problematic-145681

Gasser, U., Ienca, M., Scheibner, J., Sleigh, J., & Vayena, E. (2020, June 29). Digital tools against COVID-19: taxonomy, ethical challenges, and navigation aid. Retrieved from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landig/article/PIIS2589-7500(20)30137-0/fulltext

Gluckman, P., & Bardsley, A. (2020, April 17). The Future is Now: Implications of COVID-19 for New Zealand. Retrieved from Koi Tū: The Centre for Informed Futures: https://informedfutures.org/the-future-is-now/

Hunt, M. (2020, October 29). Asking the right questions: an interview with Canada’s stats chief, Anil Arora. Retrieved from Global government forum: https://www.globalgovernmentforum.com/interview-canada-stats-chief-anil-arora/

Kendi, I. X. (2020, April 6). What the Racial Data Show: The pandemic seems to be hitting people of colour the hardest. Retrieved from The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/coronavirus-exposing-our-racial-divides/609526/

Koetsier, J. (2020, September 3). The 100 Safest Countries for COVID-19: Updated. Retrieved from Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2020/09/03/the-100-safest-countries-for-covid-19-updated/amp/?streamIndex=1

Lally, J., Valenta, B., & Jogesh, T. (2020, June 24). Come join DataSF and help the City’s data response to COVID-19. Retrieved from DataSF: https://datasf.org/blog/datasf-hiring-analytics-engineer/

Lips, M., & Eppel, E. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on digital public services. (Working paper).

Lucius, N. (2020, June 9). COVID-19 Response and Racial Justice (presentation). Retrieved from Chi Hack Night: https://chihacknight.org/events/2020/06/09/nick-lucius.html

Mayor's Office of Data Analytics. (n.d.). NYC Recovery Data Partnership. Retrieved from NYC Analytics: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/analytics/initiatives/recovery-data-partnership.page

Ministry of Health. (2020, March 31). COVID-19 modelling and other commissioned reports. Retrieved from Ministry of Health: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/covid-19-modelling-and-other-commissioned-reports

Ministry of Social Development. (n.d.). The Privacy, Human Rights and Ethics Framework. Retrieved from Ministry of Social Development: https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/work-programmes/initiatives/phrae/index.html

National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. (2020). About the National COVID Cohort Collaborative. Retrieved from NIH: https://ncats.nih.gov/n3c/about

National Institute of Statistics and Geography, Mexico. (2020). Retrieved from Visualizador analítico para el COVID-19 (Analytical Visualizer for COVID-19): https://gaia.inegi.org.mx/covid19/

NHS Digital. (n.d.). Coronavirus (COVID-19) response transparency notice. Retrieved from NHS Digital: https://digital.nhs.uk/coronavirus/coronavirus-covid-19-response-information-governance-hub/coronavirus-covid-19-response-transparency-notice

OECD. (2020, June 11). Open Data & Covid-19: Looking forward towards government readiness & reform. Retrieved from OECD: https://www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/6th-oecd-expert-group-meeting-on-open-government-data-summary.pdf

Office for National Statistics. (2020, May 11). Which occupations have the highest potential exposure to the coronavirus (COVID-19)? Retrieved from Office for National Statistics: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/whichoccupationshavethehighestpotentialexposuretothecoronaviruscovid19/2020-05-11

PwC Legal. (2020). Key responsibilities for DPO in COVID-19 crisis. Retrieved from PwC Legal: https://www.pwclegal.be/en/news/key-responsibilities-for-dpo-in-covid-19-crisis.html

Renieris, E. (2020, April 14). The future of data governance. Retrieved from Berkman Klein Center: https://medium.com/berkman-klein-center/the-future-of-data-governance-c5723c38d70a

Robertson, G., & Sepuloni, C. (2020, April 7). A million workers supported by Govt wage subsidy. Retrieved from Beehive.govt.nz: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/million-workers-supported-govt-wage-subsidy

Royal Society. (2020). Coronavirus COVID-19. Retrieved from https://royalsociety.org/news/2020/03/coronavirus-covid-19/

Russo Carroll, S., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., Akee, R., Lucchesi, A., & Richards, J. R. (2020, June 11). Indigenous Data in the Covid-19 Pandemic: Straddling Erasure, Terrorism, and Sovereignty. Retrieved from Social Science Research Council: https://items.ssrc.org/covid-19-and-the-social-sciences/disaster-studies/indigenous-data-in-the-covid-19-pandemic-straddling-erasure-terrorism-and-sovereignty/

Social Wellbeing Agency. (n.d.). Retrieved from Data Protection and Use Policy: https://dpup.swa.govt.nz/

Statistics Netherlands. (2020, May 29). Mortality in times of corona. Retrieved from Statistics Netherlands: https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/news/2020/22/mortality-in-times-of-corona

Stats NZ. (2014, June 17). Disability survey: 2013. Retrieved from Stats NZ: https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/disability-survey-2013

Stats NZ. (2018, August 23). Strengthening data leadership across government to enable more effective public services. Retrieved from Stats NZ: https://www.stats.govt.nz/corporate/cabinet-paper-strengthening-data-leadership-across-government-to-enable-more-effective-public-services

Stats NZ. (2020, October 16). Stats NZ's guide to developing COVID-19-related questionnaires for specific populations. Retrieved from Stats NZ: https://www.stats.govt.nz/methods/guide-to-developing-covid-19-related-questionnaires-for-specific-populations

Stats NZ. (n.d.). Ngā Tikanga Paihere. Retrieved from Stats NZ: https://www.data.govt.nz/use-data/data-ethics/nga-tikanga-paihere/

The Treasury. (2020). New Zealand Activity Index. Retrieved from The Treasury: https://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/research-and-commentary/new-zealand-activity-index

United Nations. (2020, May). Data Strategy of the Secretary-General for Action by Everyone, Everywhere. 2020-22. Retrieved from United Nations.

Vendeville, G. (2020, March 27). U of T infectious disease expert's AI firm now part of Canada's COVID-19 arsenal. Retrieved from University of Toronto: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-infectious-disease-expert-s-ai-firm-now-part-canada-s-covid-19-arsenal

Vincent, B. (2020, June 30). What the COVID-19 Pandemic Is Revealing to Federal Chief Data Officers. Retrieved from Nextgov: https://www.nextgov.com/analytics-data/2020/06/what-covid-19-pandemic-revealing-federal-chief-data-officers/166517/

July 2020

August 2020

September 2020

Recommendation – improve data findability, access and sharing

Additional interventions

Recommendation – identify the most important data

Additional interventions

Recommendation – support collaboration

Recommendation – clarify governance roles

Additional interventions

Recommendation – foster expertise-based networks

Recommendation – help navigate privacy, security and ethics

Additional interventions

While the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in restrictive measures and a dramatic reduction in activity, it also empowered agencies to deliver what was needed, with freedom to explore creative solutions.

Senior leadership at Inland Revenue (IR) endorsed this approach, providing its staff the necessary licence to address the needs for data and information that was critical to managing their pandemic response. With a clear understanding of intent and boundaries, those in the organisation mobilised, focussed on delivering the most optimal means of satisfying data and information needs in the face of unprecedented demand.

Prior to the pandemic, IR had initiated a significant business transformation programme, which included a reassessment of existing data and information systems, and had helped increase awareness of the viability of infrastructure investment. One outcome had been a proposal for a centralised self-service portal to coordinate various internal reports and dashboards, improving access for senior leadership and staff across IR requiring easy access to trusted information. While it was already on track for development, this portal, the IR Intelligence Centre, was little more than a set of ideas when the COVID-19 pandemic landed in New Zealand.

The resultant demand for real-time data and information, heightened need for coordination across the organisation, and senior leadership licence for creative solutions combined to help fast-track the Intelligent Centre’s development and implementation. COVID-19 was one of the first topics added to the newly established portal, opening it to content from the Ministry of Social Development and The Treasury initially, and transforming it from a solution focussed on internal business, to a rich information resource that included high quality externally sourced content.

Once operational, a state achieved in a few days, the portal provided key IR decision-makers with up to date, more complete and quality assessed information. This meant that more timely and better informed data-driven decisions could be made in response to pandemic conditions. It also provided analysts with references to external data that they could incorporate with IR data to conduct more comprehensive analysis. Content was organised by topic and source organisation, and users at IR could opt-in to receive notifications when new material matching their preferences was added.

Following its initial success, the IR Intelligence Centre has the potential to become enduring infrastructure, more widely available, and including additional sources of data and information. Having demonstrated the value of positioning externally sourced data and information alongside internally generated information, it has helped highlight the potential of continuing to expand such resources for decision-makers.

The ability to seamlessly access data and information from other organisations during the pandemic also meant that IR did not need to produce that information themselves, and could focus more of its efforts on effective use of that information. It expanded the scale of the data and information resources at the organisation’s disposal, reflecting a wider distribution of sources, and facilitating a more resilient approach.

Crisis events like the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the criticality of data for an effective response and as part of a long-term national strategy, and that is particularly evident at the local or community level.

The effects of a crisis, and the solutions to which data can contribute, resonate in local contexts and for specific groups of people, with some of those groups more disadvantaged than others. In New Zealand, iwi and Māori, Pasifika, and people with disabilities represented three such populations at risk and adversely affected by COVID-19. The pandemic perpetuated and, in some cases, exacerbated existing data-related deficiencies.

A challenge for the communities associated with these three groups is the persistence of a government data collection approach that does not ensure sufficient visibility. A lack of visibility in data can manifest as the omission of populations altogether, or as collection at an inadequate level of quality, improper scale, or with insufficient consultation, such that the results are not available or do not reflect the data needs of communities representing those populations.

In contrast, a collection approach of inclusivity will most likely result in greater visibility in the data, which in turn allows that data to do its job and properly inform policies, interventions and other actions associated with community response and resilience in a crisis. An inclusive approach can contribute to trust and improved relationships with these communities, allowing them to fully and more equitably engage with government and other data partners.

Of particular importance in the case of indigenous populations and communities, an inclusive data collection approach can provide a means of promoting their perspectives, rights and inherent data authority, thereby facilitating data sovereignty and supporting increased self-sufficiency.

Under pressure from unprecedented demands imposed by COVID-19, government agencies, including those that did recognise the value of data reflecting disadvantaged populations, were not able to address existing shortcomings in their data collection strategies. The crisis conditions challenged their ability to implement proper planning, conduct sufficient consultation, or establish necessary design parameters to ensure widespread visibility of the communities reflecting at-risk populations. This resulted in a range of adverse effects.

Iwi and Māori: Iwi representatives reported that their communities experienced an uptick in government data collection with the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic but, without an expected level of cohesion or coordination, this resulted in increased respondent burden. Additionally, the government’s data collection efforts were perceived as only serving its own needs and delivered to its own standards, different from those of the local communities. This led to situations where data already collected by communities was re-collected by government. The result was a diminishing of trust, as it appeared Māori data sovereignty had been overlooked, and an undermining of the ability of local communities to leverage data analysis to inform local responses to the pandemic.